We’ll be back after Labor Day.

We’ll be back after Labor Day.

Today is the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition. UNESCO designated August 23 because it marks the beginning of the 1791 slave rebellion in Santo Domingo (today Haiti and the Dominican Republic) led by Toussaint L’Ouverture.

The 2017 theme, “Remember Slavery: Recognizing the Legacy and Contributions of People of African Descent,” focuses on the ways in which enslaved Africans and their descendants “influenced and continue to shape societies around the world.”

The under-told story of the Transatlantic Slave Trade is also the focus of a TED-Ed video that has garnered 2.5 million views.

For more info, go here.

Philadelphia is the City of Murals. The murals celebrate events, as well as residents who have made a difference. Few are more celebrated than John Coltrane who moved to Philadelphia in 1943. Coltrane resided in an apartment in Yorktown before buying a house in Strawberry Mansion in 1952. The house is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a National Historic Landmark.

Coltrane kicked his heroin habit and composed “Giant Steps” in that house.

In 2002, the Strawberry Mansion community, in collaboration with the Mural Arts Program, honored their former neighbor. The Pennrose Company demolished the Tribute to John Coltrane mural in 2014.

To be sure, murals come and go. However, there is too much love for Trane to let the demolition go unnoticed. It has taken a while but a new mural celebrating the life and legacy of the jazz innovator will soon be dedicated. The community is invited to add a brushstroke at a public paint day on Saturday, August 19 from 1-3 p.m., at Fairmount Park’s Hatfield House, located at 33rd Street and Girard Avenue.

So get up for the down brushstroke. Everybody get up and join the Mural Arts Philadelphia, Fairmount Park Conservancy, Strawberry Mansion Neighborhood Action Committee and All That Philly Jazz.

For more info, visit Mural Arts Philadelphia.

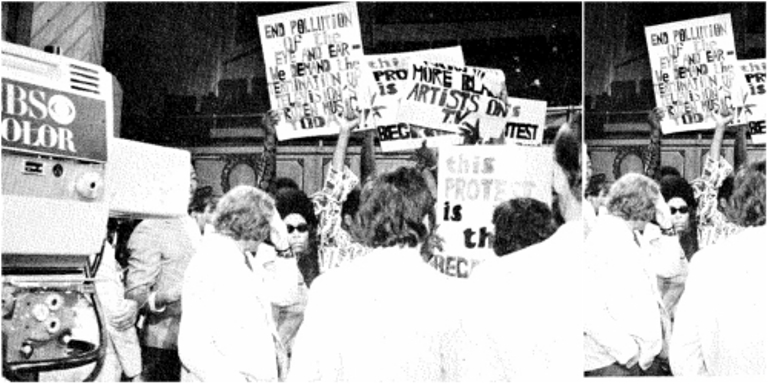

In 1970, a band of musicians sounded a call to arms over the exclusion of black jazz musicians in the mass media, specifically commercial television. Broadcast TV was the dominant medium of the era. Multi-instrumentalist Rahsaan Roland Kirk spearheaded Jazz and People’s Movement. Kirk circulated a petition in New York City jazz clubs which was signed by, among others, Lee Morgan, Charles Mingus, Andy Cyrrile, Billy Harper, Freddie Hubbard, Cecil Taylor, Elvin Jones, Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp and Roy Haynes.

The petition read, in part:

Many approaches have been used through the ages in the attempted subjugation of masses of people. One of the very essential facets of the attempted subjugation of the black man in America has been an effort to stifle, obstruct and ultimately destroy black creative genius; and thus, rob the black man of a vital source of pride and liberating strength. In the musical world, for many years a pattern of suppression has been thoroughly inculcated into most Americans. Today many are seemingly unaware that their actions serve in this suppression – others are of course more intentionally guilty. In any event, most Americans for generations have had their eyes, ears and minds closed to what the black artist has to say.

Obviously only utilization of the mass media has enabled white society to establish the present state of bigotry and whitewash. The media have been so thoroughly effective in obstructing the exposure of true black genius that many black people are not even remotely familiar with or interested in the creative giants within black society.

[…]

Action to end this injustice should have begun long ago. For years only imitators and those would sell their souls have been able to attain and sustain prominence on the mass media. Partially through the utilization of an outlandish myth, that in artistic and entertainment fields bigotry largely no longer exists, and by showrooming those few blacks who have sold out, the media have so far escaped the types of response that such suppression and injustice should and now will evoke.

Jazz and People’s Movement took action. Demonstrators disrupted tapings of The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, The Dick Cavett Show and The Merv Griffin Show. On signal, group members played noisemakers and instruments that they had smuggled into the studios. They also passed out leaflets and displayed placards.

Also in the ‘70s, trumpeter, arranger and all-around musical genius Quincy Jones was on the board of the Institute of Black American Music whose mission was similar to Jazz and People’s Movement.

Fast forward to today, the multi-Grammy winning Jones is taking a journey into jazz and beyond with Qwest TV, the world’s first subscription video-on-demand platform dedicated to jazz from bebop to hip-hop. In a statement, Jones said:

The dream of Qwest TV is to let jazz and music lovers everywhere experience these incredibly rich and diverse musical traditions in a whole new way.

At my core, I am a bebopper, and over the course of my seventy-year career in music I have witnessed firsthand the power of jazz – and all of its off-spring from the blues and R&B to pop, rock and hip-hop, to tear down walls and bring the world together. I believe that a hundred years from now, when people look back at the 20th century, they will view Bird, Miles and Dizzy, as our Mozart, Bach, Chopin and Tchaikovsky, and it is my hope that Qwest TV will serve to carry forth and build on the great legacy that is jazz for many generations to come.

The streaming service will launch in fall 2017. For more info, visit Qwest TV.

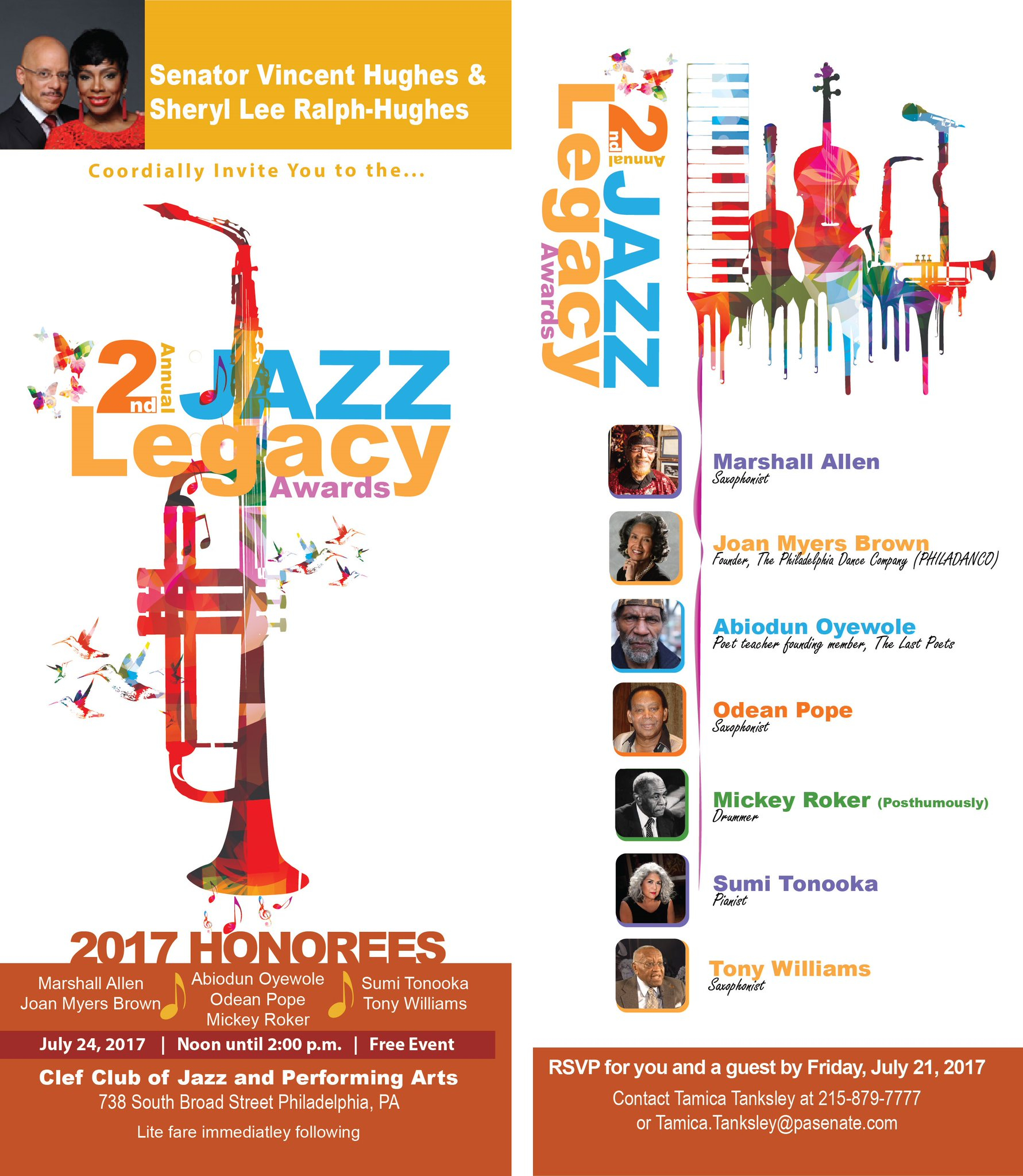

On Monday, July 24, 2017, the jazz community, spearheaded by state Sen. Vincent Hughes and Sheryl Lee Ralph-Hughes, will celebrate seven pioneers in the world of arts and culture:

The event is free but you must RSVP by contacting Tamica Tanksley via email or by phone at (215) 879-7777.

In June 2001, jazz scholar Ashley Kahn interviewed Alice Coltrane.

Mrs. Coltrane shared memories of her legendary husband John Coltrane, including his views of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X:

A lot was going on in the ’60s—black empowerment, civil rights, new jazz music was becoming the New Thing, which also had a political edge. How did John look upon all of that at the time—especially race politics? Was he with Dr. King or more with Malcolm [X]?

He was very interested in the civil-rights movement. He appreciated both men from their different perspectives. He did see the unity in what they were trying to achieve, basically almost the same thing, taking different directions to reach that point of achievement.

He knew that Dr. Martin Luther King was an intelligent man, who would’ve probably found his quest in civil rights more horrible, more horrendous, by going through the system as a lawyer or a professor. John felt that [King] as a preacher could reach the heart of the people. And he felt that this was very good, that it was an asset, that he would be able to lead the people based on the spiritual sense instead of the civic, intellectual, legalistic. John felt if you can talk to their heart you’ll get their support, and you’ll get them to believe in what you’re doing.

About Malcolm, I know John had attended some of his talks that were in our area. Once he came back and I asked him, “How was the lecture?” and he said he thought it was superb. Different approaches to the same goal, telling the people [to] be wise, try to get some kind of economic freedom, be self-sufficient, depend on yourself, strengthen your family ties. Things like that, not even involved with religion, just basic areas of improvement so that you can make yourself a strong force for the good that needs to be achieved. He told me that he appreciated the way that when the really tough questions were asked from the audience, every one was answered with an intelligence which the people could comprehend.

I know that some musicians who were around at the time were more militant. How did John feel about that?

He would not be a part of it, and this is what many people wanted him to do. They’d say, “Why don’t you take your horn, use it as an instrument to rally people together, to awaken consciousness in these people to really stand and fight for their rights?” He just said, “That’s not the way for me to go with this music.” It was not the way for him, to take his music into a militant zone to try to stress a point. If anything, we saw him going up. I would imagine his philosophy would be closer to Martin Luther King Jr.: Let me try to reach your heart, your spirit and your soul, and then we can move forward uniformly as a people and accomplish great things.

He didn’t prefer violence to peace, and he was very disturbed by the consequences [of the riots in the mid-1960s] and all the people who were getting hurt in the rioting. I believe he called us once [when] he was out of town when those [riots] were happening. He was mainly on the phone with his mother, because she was with us at the time and she was quite upset about it.

The full transcript is available here.

Earlier this month, I attended a panel discussion on “Art in Public Space” held in the Hamilton Garden of the Kimmel Center. As I waited for the program to start, I checked out the view from the top floor. What I saw left a hole in my heart.

The hole is where Philadelphia International Records once stood.

Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff have earned their place in history.

Sadly, the building that held the stories of the songwriters, musicians, producers and arrangers is now lost to history. For the love of money, African Americans’ cultural heritage was erased from public memory.

Gamble and Huff sold the historic building to Dranoff Properties which plans to build a luxury hotel and condos for the one percent. Three years after the demolition of “309,” there’s just a hole in the ground. The reason: Dranoff Properties is waiting for a corporate welfare check to the tune of $19 million before breaking ground on the “biggest, tallest and most expensive” project the company has ever done.

In the poorest big city in the country, spending taxpayers’ money to further enrich the rich is the sound of Philadelphia.

May is Preservation Month, a time to celebrate places that matter to you. On May 6, I led a Jane’s Walk, “Ridge Avenue Stroll through Philly’s Jazz History.” The first stop was the legendary Blue Note. The Ray Bryant Trio was the Blue Note’s house band. Interestingly, Bryant co-wrote the smash hit, “Madison Time,” which was released in 1959.

The highlight of the stroll was 2125 Ridge Avenue, the former location of the Checker Café, a “black and tan” (read: racially integrated) jazz club. The nightclub’s motto was “Good Food. Good Cooks. Good Service.” One of the servers was a teenage singing waitress named Pearl Bailey.

Since October 2016, I’ve been locked in battle with the Philadelphia Housing Authority which wants to demolish the building that has been a visual anchor for more than 100 years. The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission agreed with me the building is of historical significance. Last week, PHA signed a programmatic agreement that saves the building for now. Under the agreement, PHA must stabilize the building.

I say for now because PHA has made it clear it wants to demolish the building. I guess it doesn’t fit their “vision” for a revitalized Ridge Avenue. In an area full of vacant lots, PHA wants to replace a building that may be eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places with yet another vacant lot.

I encouraged the 40+ people who participated in my Jane’s Walk to make some noise and tell decision-makers that this place matters. If you care about preserving Philadelphia’s cultural heritage, DM me on Twitter or email to phillyjazzapp[@]gmail.com.

All That Philly Jazz Director Faye Anderson leads a walking tour, “Ridge Avenue Stroll through Philly’s Jazz History.”

In the wake of the Great Migration, the demographics of North Philadelphia’s Sharswood neighborhood changed. The new residents fueled the growth of commercial establishments along Ridge Avenue that catered to African Americans. From the Blue Note (15th Street) to the Crossroads Bar (23rd Street), Ridge Avenue was a jazz corridor and entertainment district.

Ridge Avenue was also a safe haven from the indignities of racial discrimination. African American entertainers performed in Center City at places such as the Earle Theater and Ciro’s, but they were not allowed to stay in downtown hotels. The Negro Motorist Green Book helped black travelers navigate Jim Crow laws in the South and racial segregation in the North.

Published from 1936 to 1966, the “Green Book” listed hotels, restaurants, night clubs, beauty parlors and other services that enabled African Americans to “vacation without aggravation.”

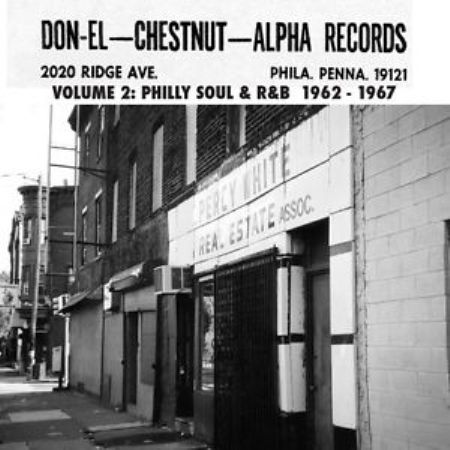

Our stroll will begin at the legendary Blue Note. We walk around the corner and stop at the Nite Cap. We then head north up Ridge Avenue, stopping at the Bird Cage Lounge and Don-El Records.

Moving along, we check out the Hotel LaSalle which was listed in the “Green Book” and advertised in the NAACP’s Crisis magazine.

We then stop by V-Tone Records, the LaSalle Beauty Parlor and Butler’s Paradise Café (listed in the “Green Book”).

Next stops: Ridge Cotton Club (listed in the “Green Book”) and the Pearl Theatre.

The highlight of the walk is the Checker Café, one of the last vestiges of the Ridge Avenue entertainment district.

We end our stroll at Mr. Chip’s Bar and Irene’s Café (listed in the “Green Book”).

We will walk the streets where future jazz legends such as Pearl Bailey, Clifford Brown, Cab Calloway, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, Philly Joe Jones, Lee Morgan, Charlie Parker and Nancy Wilson once roamed. For more information, contact Faye at greenbookphl@gmail.com.

The 2017 Jazz Masters are in the history book. With threats to its funding, will the National Endowment for the Arts itself be history? First, a recap of #NEAJazz17.

The NEA conferred the NEA Jazz Master award, the nation’s highest honor in jazz, on Dee Dee Bridgewater, Ira Gitler, Dave Holland, Dick Hyman and Dr. Lonnie Smith.

The celebration kicked off with the NEA Jazz Masters Listening Party at NPR, moderated by Jason Moran. The Jazz Masters and Fitz Gitler (representing his father) were joined in conversation by musicians whose lives they have influenced. They generously – and humorously – shared stories about their musical journey.

On April 3, the NEA held a tribute concert in the Jazz Masters’ honor at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

While joy filled the air, there are some discordant notes. If the NEA is defunded, the Class of 2017 may be the last Jazz Masters. The New York Times reported:

President Trump’s budget proposal last month called for eliminating the endowment entirely — the first time any president has proposed such a step. While some members of Congress in his own Republican Party have opposed the move, it is a reminder of the agency’s vulnerability.

[…]

Created in 1965, the endowment provides funding to arts organizations, including jazz projects that are supported with dozens of grants each year. It also sends nearly half of its funding budget to regional arts organizations that disperse funds themselves.

The NEA can’t advocate for its own survival. So, as jazz and film critic Gary Giddins noted, it’s “jazz advocacy of the hip, by the hip and for the hip shall not perish from the Earth.”

Truth is, NEA is about more than jazz.

The arts matter. Art transforms lives and communities. The arts are also an economic driver. So let’s make some noise. Here’s what you can do in two minutes to help #SavetheNEA.