Tag Archives: Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968)

On Vacation

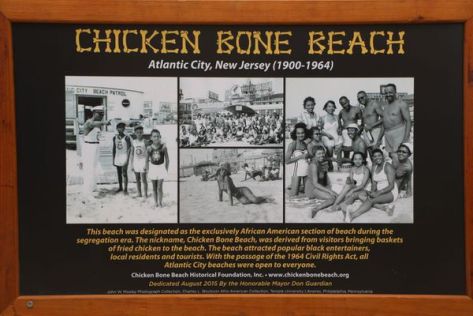

In September, I will lead a walking tour of Green Book sites in Philadelphia. The stops include the Douglass Hotel which offered transportation to Atlantic City, or more accurately, to Chicken Bone Beach.

After complaints from white bathers, African Americans were restricted to a stretch of the Atlantic City beach near Convention Hall. The segregated area became known as Chicken Bone Beach.

This two-part audio doc provides an overview of Chicken Bone Beach and the entertainment district that became a magnet for black vacationers, day-trippers and luminaries such as Martin Luther King Jr., Louis Armstrong, Nina Simone, Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Sammy Davis Jr.

For more info, visit Chicken Bone Beach.

Fourth of July 2019

On July 5, 1852, before the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society in Rochester, New York, Frederick Douglass asked, “What to the slave is the Fourth of July?”

What indeed?

Today we often communicate via memes, but the message is the same.

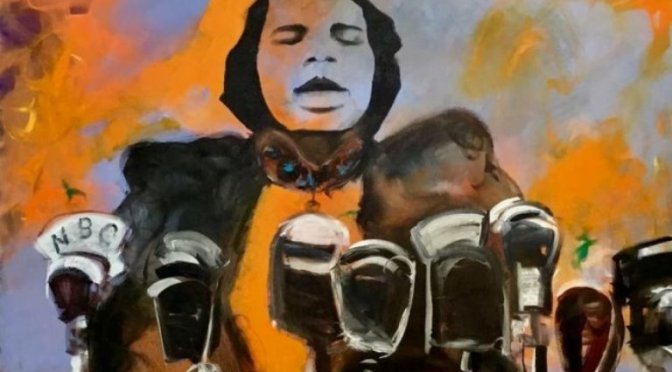

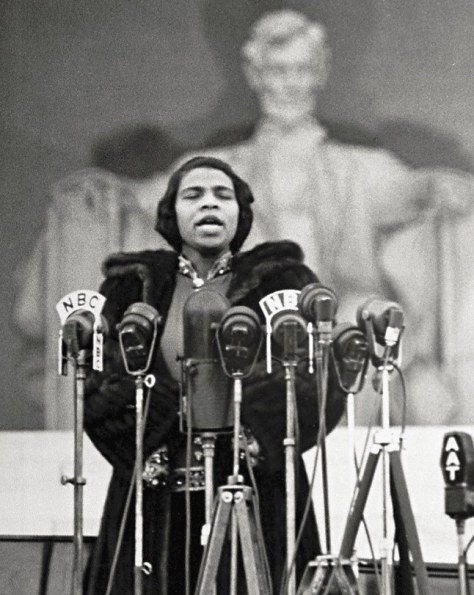

Remembering Marian Anderson

Given the givens, some folks have called for a “do-over” of Black History Month 2019. I want to close out February on a high note by remembering Marian Anderson.

The name Marian Anderson has been part of my life from Day One. An older-now-deceased sister was named Marian. As a schoolgirl, I was puzzled when I would hear my teachers say her name. Of course I would later learn they were referring to the world-renowned contralto who inspired a generation of civil rights activists, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

In a high school essay, 15-year-old Martin wrote:

Black America still wears chains. The finest Negro is at the mercy of the meanest white man. Even winners of our highest honors face the class color bar. Look at a few of the paradoxes that mark daily life in America. Marian Anderson was barred from singing in the Constitution Hall, ironically enough, by the professional daughters of the very men who founded this nation for liberty and equality. But this tale had a different ending. The nation rose in protest, and gave a stunning rebuke to the Daughters of the American Revolution and a tremendous ovation to the artist, Marian Anderson, who sang in Washington on Easter Sunday and fittingly, before the Lincoln Memorial. Ranking cabinet members and a justice of the Supreme Court were seated about her. Seventy-five thousand people stood patiently for hours to hear a great artist at a historic moment. She sang as never before with tears in her eyes. When the words of “America” and “Nobody Knows De Trouble I Seen” rang out over that great gathering, there was a hush on the sea of uplifted faces, black and white, and a new baptism of liberty, equality and fraternity. That was a touching tribute, but Miss Anderson may not as yet spend the night in any good hotel in America. Recently she was again signally honored by being given the Bok reward as the most distinguished resident of Philadelphia. Yet she cannot be served in many of the public restaurants of her home city, even after it has declared her to be its best citizen.

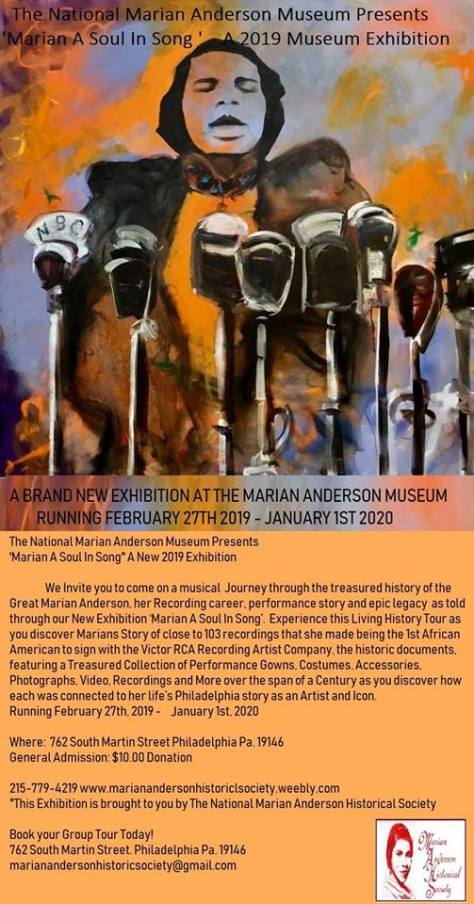

That was then. Ms. Anderson is now an American icon who will be celebrated in her home city with a new exhibition, “Marian: A Soul In Song,” presented by the National Marian Anderson Historical Society.

The exhibition features a collection of the opera singer’s performance gowns, costumes and accessories, photographs, video and recordings. The exhibition runs from February 27, 2019 to January 1, 2020. For more information and tickets, visit the Marian Anderson Museum & Historical Society.

Remembering Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. was born on January 15, 1929 in Atlanta. An HBO documentary includes scenes from his last birthday celebration in 1968.

Xernona Clayton said she organized the office party to “cheer up” the civil rights leader. For information about King in the Wilderness, go here.

Happy birthday, Dr. King. We miss you but your legacy lives on in our determination to “keep moving.”

Franklin Motor Inn

The Franklin Motor Inn was located off Benjamin Franklin Parkway at 22nd Street and Spring Garden.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stayed here on his final visit to Philadelphia. It is also where most of the acts performing at the legendary Uptown Theater stayed. From Philadelphia magazine:

Built in 1959, the hotel used to be called the Franklin Motor Inn. New York boxing promoters used to put up their guys here. Hookers idled, businessmen prowled, and the bar used to stay open till 4 a.m.

There was an A-list presence too. The last time Martin Luther King ever visited Philly, according to a 1994 piece in the Philadelphia Tribune, he spent the day sick in bed at the Franklin Motor Inn, his favorite hotel in the city. Joe Frazier, a regular, always sat in the same seat, on the far right end of the bar. (Marvis Frazier tells me his father ate breakfast at the hotel at least once a week for more than 30 years, but really came to “play the numbers.”)

Blue Note Salon

On December 8, 1956, the Miles Davis Quintet, featuring Miles Davis (trumpet), John Coltrane (tenor saxophone), Red Garland (piano), Paul Chambers (bass) and Philly Joe Jones (drums) performed at the Blue Note. The set was featured on the Mutual Network live remote radio broadcast, Bandstand, U.S.A.

That same night, the police raided “the town’s swankiest jazz emporium.” The Blue Note was a “black and tan” club, an integrated nightspot where blacks and whites socialized on an equal basis. As such, it was the target of police harassment.

From the beginning, jazz was a tool for social change. Jazz musicians’ unbowed comportment created a cultural identity that was a steppingstone to the Civil Rights Movement. In remarks to the 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said jazz is “triumphant music”:

Jazz speaks for life. The Blues tell the story of life’s difficulties, and if you think for a moment, you will realize that they take the hardest realities of life and put them into music, only to come out with some new hope or sense of triumph.

This is triumphant music.

Modern jazz has continued in this tradition, singing the songs of a more complicated urban existence. When life itself offers no order and meaning, the musician creates an order and meaning from the sounds of the earth which flow through his instrument.

It is no wonder that so much of the search for identity among American Negroes was championed by Jazz musicians. Long before the modern essayists and scholars wrote of racial identity as a problem for a multiracial world, musicians were returning to their roots to affirm that which was stirring within their souls.

Much of the power of our Freedom Movement in the United States has come from this music. It has strengthened us with its sweet rhythms when courage began to fail. It has calmed us with its rich harmonies when spirits were down.

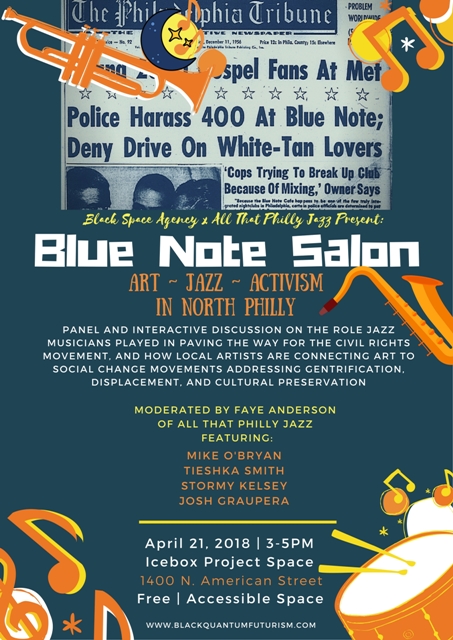

On April 21, 2018, All That Philly Jazz and Black Quantum Futurism will present the “Blue Note Salon” which pays homage to jazz musicians’ legacy of resistance. The community discussion will feature creative change makers who work on social justice issues. Their work is at the intersection of art, community engagement and social change.

The event is free and open to the public. To RSVP, go here.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968)

John Coltrane and Civil Rights

In June 2001, jazz scholar Ashley Kahn interviewed Alice Coltrane.

Mrs. Coltrane shared memories of her legendary husband John Coltrane, including his views of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X:

A lot was going on in the ’60s—black empowerment, civil rights, new jazz music was becoming the New Thing, which also had a political edge. How did John look upon all of that at the time—especially race politics? Was he with Dr. King or more with Malcolm [X]?

He was very interested in the civil-rights movement. He appreciated both men from their different perspectives. He did see the unity in what they were trying to achieve, basically almost the same thing, taking different directions to reach that point of achievement.

He knew that Dr. Martin Luther King was an intelligent man, who would’ve probably found his quest in civil rights more horrible, more horrendous, by going through the system as a lawyer or a professor. John felt that [King] as a preacher could reach the heart of the people. And he felt that this was very good, that it was an asset, that he would be able to lead the people based on the spiritual sense instead of the civic, intellectual, legalistic. John felt if you can talk to their heart you’ll get their support, and you’ll get them to believe in what you’re doing.

About Malcolm, I know John had attended some of his talks that were in our area. Once he came back and I asked him, “How was the lecture?” and he said he thought it was superb. Different approaches to the same goal, telling the people [to] be wise, try to get some kind of economic freedom, be self-sufficient, depend on yourself, strengthen your family ties. Things like that, not even involved with religion, just basic areas of improvement so that you can make yourself a strong force for the good that needs to be achieved. He told me that he appreciated the way that when the really tough questions were asked from the audience, every one was answered with an intelligence which the people could comprehend.

I know that some musicians who were around at the time were more militant. How did John feel about that?

He would not be a part of it, and this is what many people wanted him to do. They’d say, “Why don’t you take your horn, use it as an instrument to rally people together, to awaken consciousness in these people to really stand and fight for their rights?” He just said, “That’s not the way for me to go with this music.” It was not the way for him, to take his music into a militant zone to try to stress a point. If anything, we saw him going up. I would imagine his philosophy would be closer to Martin Luther King Jr.: Let me try to reach your heart, your spirit and your soul, and then we can move forward uniformly as a people and accomplish great things.

He didn’t prefer violence to peace, and he was very disturbed by the consequences [of the riots in the mid-1960s] and all the people who were getting hurt in the rioting. I believe he called us once [when] he was out of town when those [riots] were happening. He was mainly on the phone with his mother, because she was with us at the time and she was quite upset about it.

The full transcript is available here.