Election Day is Tuesday, November 6. Be careful how you vote.

As we know, stuff happens. So if you encounter problems at your polling place, call 866-OUR-VOTE.

Election Day is Tuesday, November 6. Be careful how you vote.

As we know, stuff happens. So if you encounter problems at your polling place, call 866-OUR-VOTE.

On November 11, 1966, John Coltrane gave his final performance in Philadelphia at Mitten Hall.

Mitten Hall will again be filled with joyful noise as the community tells Temple University: We Shall Not Be Moved.

Some background: On March 6, Temple will hold an “informational town hall” to discuss its proposal to put a 35,000-seat football stadium in the heart of an African American residential neighborhood. Temple has been planning this project for nearly two years. President Richard Englert claims Curtis J. Moody, lead architect with Moody Nolan, met with community members “to hear their concerns and has worked to integrate those comments into the designs.” Unless Moody has designed a stealth stadium, there is no way he has integrated the concerns of a community that understands a football stadium is displacement by design.

Temple’s first-ever public forum comes on the heels of a community town hall meeting convened by Black Clergy of Philadelphia and Vicinity, Philadelphia NAACP and Stadium Stompers.

Between chants of “We Shall Not Be Moved,” there was testimony from diverse stakeholders, including Mary Stricker, a sociology professor. Prof. Stricker noted the Faculty Senate passed a resolution by a 24-1 vote opposing Temple’s fantasy football scheme:

I really think this is a bad idea not only because it is a financial risk, but also because it’s in the worst interest of the surrounding community. Temple owes something to the community that has been hosting it for all these years.

Stricker added:

Temple Faculty say no new stadium. We are strong, united and determined in this fight.

Pastor Jay Broadnax, president of Black Clergy of Philadelphia and Vicinity, said:

We love football but we’re calling a timeout. We love football but the people in this community will not be a football, passed, punted, kicked and carried across the city line in order for institutions to score profit points or get land grab wins.

The proposed stadium would be located in a neighborhood that has been subject to racial segregation, redlining and neglect. Rev. Gregory Holston, executive director of Philadelphians Organized to Witness, Empower and Rebuild (POWER), observed:

For 40 years, they have disinvested in North Philadelphia. You couldn’t get a mortgage. You couldn’t get a loan. You couldn’t get a home improvement loan. You couldn’t get a loan to start a business. But however today, they got all the money to make a stadium right in your backyard.

There’s something wrong with that. Whenever they start to pour money into a neighborhood, they want to push out black folks. … Race is dug deep in this thing. Race is a factor in this thing. This stadium is about moving black folks from North Philadelphia.

Rev. William Moore, pastor of Tenth Memorial Baptist Church, captured the mood of the hundreds who turned out in the rain for the community meeting. Echoing a local resident who said the stadium design is akin to “putting a whale in a goldfish bowl,” Rev. Moore said:

If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit. If it doesn’t fit, don’t force it.

Can I get an Amen?

In June 2001, jazz scholar Ashley Kahn interviewed Alice Coltrane.

Mrs. Coltrane shared memories of her legendary husband John Coltrane, including his views of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X:

A lot was going on in the ’60s—black empowerment, civil rights, new jazz music was becoming the New Thing, which also had a political edge. How did John look upon all of that at the time—especially race politics? Was he with Dr. King or more with Malcolm [X]?

He was very interested in the civil-rights movement. He appreciated both men from their different perspectives. He did see the unity in what they were trying to achieve, basically almost the same thing, taking different directions to reach that point of achievement.

He knew that Dr. Martin Luther King was an intelligent man, who would’ve probably found his quest in civil rights more horrible, more horrendous, by going through the system as a lawyer or a professor. John felt that [King] as a preacher could reach the heart of the people. And he felt that this was very good, that it was an asset, that he would be able to lead the people based on the spiritual sense instead of the civic, intellectual, legalistic. John felt if you can talk to their heart you’ll get their support, and you’ll get them to believe in what you’re doing.

About Malcolm, I know John had attended some of his talks that were in our area. Once he came back and I asked him, “How was the lecture?” and he said he thought it was superb. Different approaches to the same goal, telling the people [to] be wise, try to get some kind of economic freedom, be self-sufficient, depend on yourself, strengthen your family ties. Things like that, not even involved with religion, just basic areas of improvement so that you can make yourself a strong force for the good that needs to be achieved. He told me that he appreciated the way that when the really tough questions were asked from the audience, every one was answered with an intelligence which the people could comprehend.

I know that some musicians who were around at the time were more militant. How did John feel about that?

He would not be a part of it, and this is what many people wanted him to do. They’d say, “Why don’t you take your horn, use it as an instrument to rally people together, to awaken consciousness in these people to really stand and fight for their rights?” He just said, “That’s not the way for me to go with this music.” It was not the way for him, to take his music into a militant zone to try to stress a point. If anything, we saw him going up. I would imagine his philosophy would be closer to Martin Luther King Jr.: Let me try to reach your heart, your spirit and your soul, and then we can move forward uniformly as a people and accomplish great things.

He didn’t prefer violence to peace, and he was very disturbed by the consequences [of the riots in the mid-1960s] and all the people who were getting hurt in the rioting. I believe he called us once [when] he was out of town when those [riots] were happening. He was mainly on the phone with his mother, because she was with us at the time and she was quite upset about it.

The full transcript is available here.

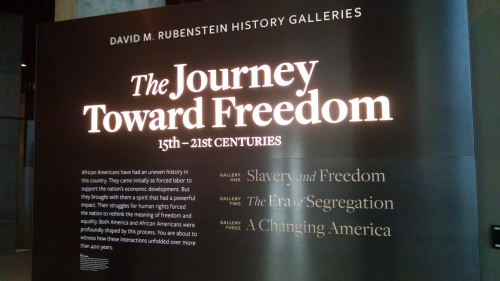

February is Black History Month. This year’s commemoration is special because we are still celebrating the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

I have visited the museum twice; my next visit is later this month. The museum can be overwhelming so I methodically focus on one floor at a time, beginning with the History Galleries.

It is as emotionally wrenching as you would imagine. It is also motivating and inspiring. I thanked the ancestors for surviving the brutality of slavery and maintaining their humanity, their “soul value.” I am empowered by their enduring legacy of struggle and resistance.

Last week, I checked out the Culture Galleries.

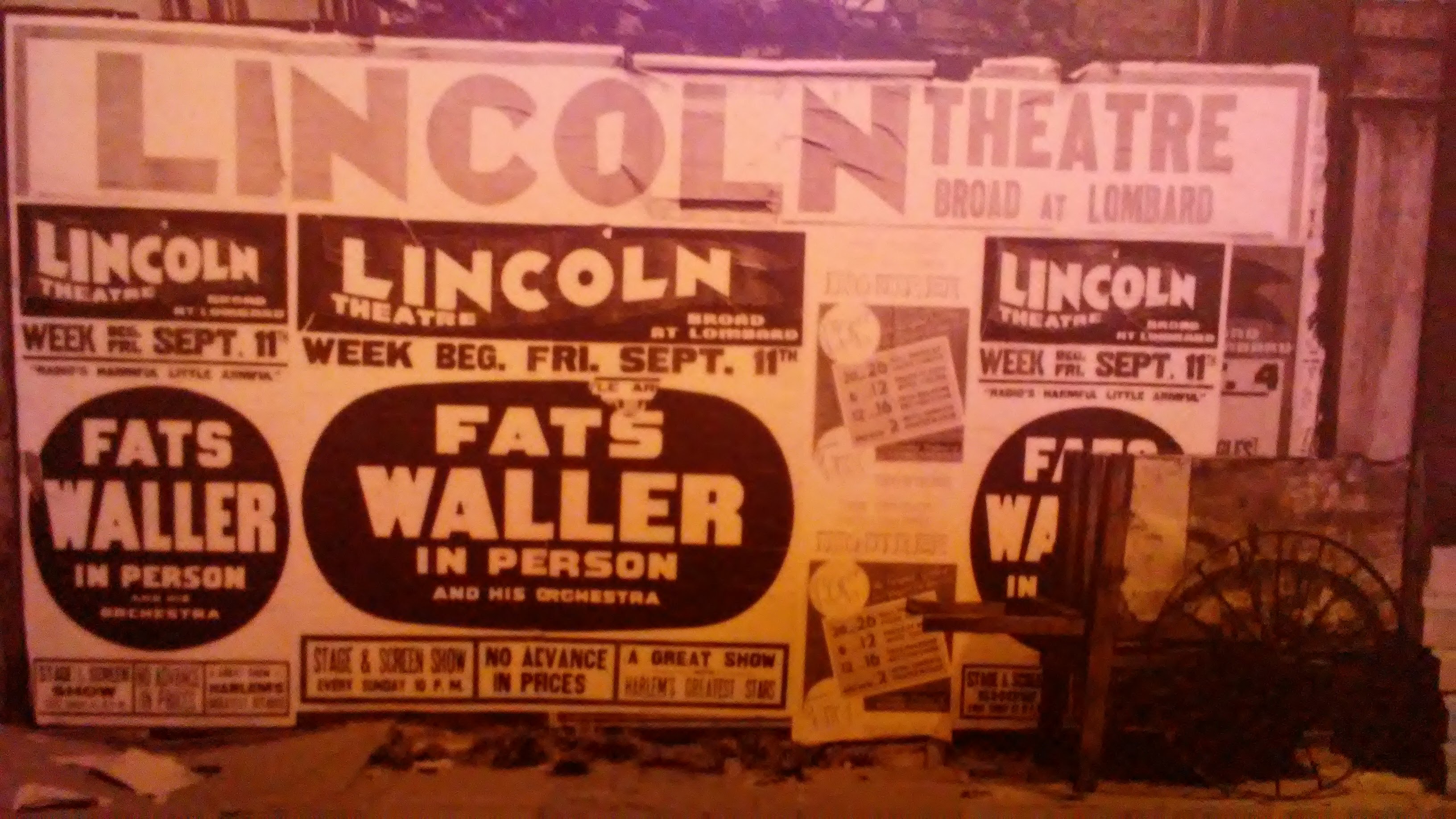

It was sheer joy to experience black culture in all its glory – music, fashion, dance, culinary and visual arts, as well as the performing arts. Philadelphia’s music legends are in the house, including Marian Anderson, John Coltrane, Dixie Hummingbirds, Kenny Gamble, Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, Leon Huff, Patti LaBelle, Paul Robeson and Sister Rosetta Tharpe. There’s an image of a billboard advertising an appearance by Fats Waller at the Lincoln Theater, a Philly landmark.

I ended each visit at Contemplative Court where I sat and, well, contemplated how we got over.

September 23rd marks the 90th anniversary of the birth of legendary saxophonist John Coltrane. It’s hard to believe but Coltrane has been dead longer than he was alive.

Trane’s life and legacy will be celebrated during nine days of free events, including film screenings, concerts, lectures and exhibitions. The festivities are organized by the Philadelphia Jazz Project in collaboration with Temple University Libraries, WRTI, PhillyCAM, Jazz Near You, among other partners.

The highlights include:

For more information, visit Philadelphia Jazz Project.

On the first day of summer, I had to report for jury duty at the Juanita Kidd Stout Center for Criminal Justice. As I stood in line to go inside the Jury Assembly Room, I noticed a panoramic mural. I made a mental note to check it out during the break.

Words cannot convey my shock and awe to discover some of the images depict Philadelphia’s legendary jazz clubs, including the Blue Note, the Showboat and Pep’s.

It is clear the details only could have come from folks who were there. So it was no surprise to learn the mural was conceived by Doug Cooper in collaboration with “Philadelphia elderly.” Cooper wrote:

I brought together more than 40 elderly residents to complete it, and I worked jointly with them at the Center in the Park in the Germantown district of Philadelphia. Local artist, Deborah Zwetsch and I assembled their memories over the previous 80 years.

[…]

The memories of the elderly are highly personal. Some are sentimental, some painful, some humorous, some ordinary.

There is nothing ordinary about the depiction of the Ridge Avenue jazz corridor.

Ridge Avenue is ground zero in the Philadelphia Housing Authority’s plan to transform the Sharswood neighborhood. There is widespread concern that PHA has no plan to preserve the neighborhood’s cultural heritage and historic resources.

Cooper’s mural, showcasing Pep’s, the Showboat, Blue Horizon, Uptown Theater and jazz clubs on Ridge Avenue, tells part of the story of Philadelphia’s rich jazz heritage. We must capture the rest of the story while the folks who were there are still here. If we don’t, their stories will be lost for current and future generations.

It’s been more than a decade in the making, the National Museum of African American History and Culture will open on September 24. Founding Director Lonnie Bunch wrote:

After 13 years of hard work and dedication on the part of so many, I am thrilled. In a few short months visitors will walk through the doors of the museum and see that it is a place for all people. We are prepared to offer exhibitions and programs to unite and capture the attention of millions of people worldwide. It will be a place where everyone can explore the story of America through the lens of the African American experience.

The National Museum of American History is asking citizen curators to vote on photos from its Archives Center that reflect the diversity of the African American experiences. Twenty-five photos, six of which selected by the public, will go on display in September to commemorate the opening of the new museum. For more information, visit http://s.si.edu/PhotoVote1. Voting closes May 27 at midnight ET.

To say I can’t wait is an understatement. Even though I get no closer than the “No Trespassing” sign, I stop by the museum on every trip to DC.

On Opening Day, the National Museum of African American History and Culture will be open for 24 hours. I plan to skip President Barack Obama’s ribbon cutting and visit after midnight. I hope to spend some quiet time in the Contemplative Court reflecting on the ancestors and their incredible stories of faith, struggle and triumph.

Great Gosh A’Mighty! NMAAHC has been a long time coming.

Oscar-nominated director Lee Daniels will direct a documentary about the legendary Harlem showplace, “The Apollo Theater Film Project.”In keeping with the Apollo’s tradition of audience participation, the project is crowdsourced:

If you or someone you know has visual or audio-visual material documenting the APOLLO THEATER or the neighborhood of HARLEM, we want to hear from you! We are looking for film footage, photographs and audio recordings to help tell this remarkable story.

Daniels wants you to go to the website and “help a brother out.”

I had a visceral response to news that City Councilman Mark Squilla introduced a bill that would impose new rules for a “special assembly occupancy” license. Among other things, applications for an SAO license must be approved by the Philadelphia Police Department. Promoters and venue operators would be required to provide the police department with the “full name, address and phone number of all performance acts scheduled to perform during the promoted event or special event.”

There is concern the bill is racially motivated, i.e., it’s targeting venues that promote hip-hop artists. Capt. Francis Healy, the PPD’s legal adviser, told the Philadelphia Inquirer Squilla’s bill has “nothing to do with race,” adding:

I could see where it could be [interpreted as such].

The police department has a sordid history with black musicians. During Philly’s jazz heyday, clubs were under police surveillance. Jazz venues would be raided because black and white patrons were fraternizing. In a piece for Hidden City Philadelphia, Jack McCarthy shared a news report from 1949:

A preholiday raid by… detectives… once again smacks of racial prejudice on part of the law enforcers… [The] Downbeat is the favorite hangout for the be-bop fans and is the only downtown spot which never has discriminated against Negro patronage. In fact, crowds here have been interracial in character, attracting everybody from the intelligentsia to the rabid be-bop fan.

Nat Segall, former owner of the Downbeat who originally established the room, gave it up a year ago rather than give in to certain political powers who urged he adopt a segregation policy for the room. When he refused to give in, Segall, a former musician now in the booking business, was pestered by police raids and finally sold out.

Charges of underage drinkers at the Downbeat, basis for the raid, is a weak one when you see the patronage of purity-white places… you’ll find teenagers any night of the week in practically every night club in town.

Police harassment put the legendary club out of business. Philadelphia police and federal narcotics agents hounded Billie Holiday. Indeed, Lady Day was the first casualty of the War on Drugs.

On Nov. 17, 1955, Ray Charles and his entire band were arrested on drug charges. Although the charges were later dropped, Brother Ray vowed to never again perform in Philadelphia.

Sixty years later, there are echoes of Ray Charles’s concern about the climate for musicians. As currently written, the police department would maintain a registry of performers. Musicians are posting on social media that if Squilla’s bill passes, they will skip Philly.

Heard enough? Then take note and join the protest against Bill No. 160016 at City Hall on Thursday, Feb. 4 at 9 a.m. For more information, visit March for Musicians Against Bill #160016 on Facebook.

Don’t let Squilla stop the music.

UPDATE: Councilman Mark Squilla’s bill struck a discordant note. At a hastily-arranged meeting with music industry leaders, Squilla said:

There’s a distrust between some performers and the government, a feeling of “big brother watching you.” That was not my intent.

In the wake of the social media backlash, Squilla will “withdraw the bill and start over from scratch.” Strike up the band and let the music play.