All That Philly Jazz Director Faye Anderson was recently interviewed by the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. The federal agency “promotes the preservation, enhancement, and sustainable use of our nation’s diverse historic resources, and advises the President and the Congress on national historic preservation policy.” The following is an excerpt from the interview.

What led you to your field?

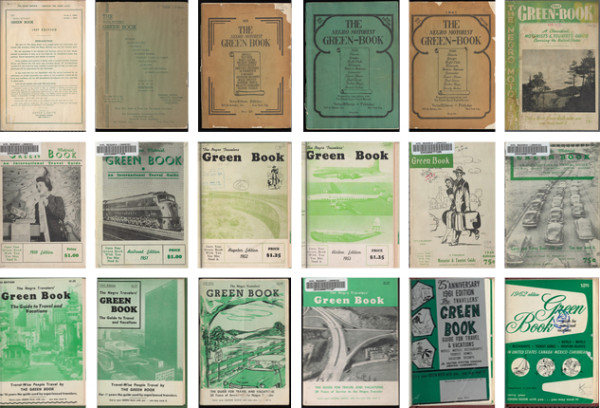

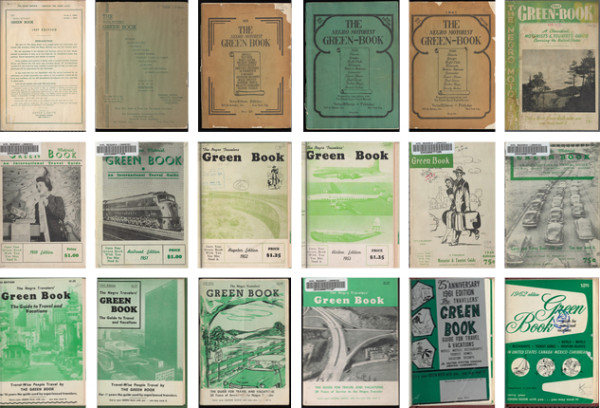

I am a lifelong social justice activist. But I am an “accidental” preservationist. My interest in historic preservation was piqued by the historical marker that notes Billie Holiday “often lived here” when she was in Philadelphia. I went beyond the marker and learned that “here” was the Douglass Hotel. I wanted to know why Lady Day stayed in a modest hotel when a luxury hotel, the Bellevue-Stratford (now the Bellevue Philadelphia), is located just a few blocks away. The Douglass Hotel was first listed in The Negro Motorist Green Book in 1938. The Green Book was a travel guide that helped African Americans navigate Jim Crow laws in the South and racial segregation in the North.

How does what you do relate to historic preservation?

There are few extant buildings associated with Philadelphia’s jazz legacy. In cities across the country, jazz musicians created a cultural identity that was a stepping stone to the Civil Rights Movement. All That Philly Jazz is a crowdsourced project that is documenting untold or under-told stories. At its core, historic preservation is about storytelling. The question then becomes: Whose story gets told? The buildings that are vessels for African American history and culture typically lack architectural significance. While unadorned, the buildings are places where history happened. They connect the past to the present.

Why do you think historic preservation matters?

For me, historic preservation is not solely about brick-and-mortar. I love old buildings. I also love the stories old buildings hold. To borrow a phrase from blues singer Little Milton, if walls could talk, they would tell stories of faith, resistance, and triumph. Historic preservation is about the power of public memory. It’s about staking African Americans’ claim to the American story. A nation preserves the things that matter and black history matters. It is, after all, American history.

What courses do you recommend for students interested in this field?

Historic preservation does not exist in a vacuum. The built environment reflects social inequities. I recommend students take courses that will help them understand systemic racism and how historic preservation perpetuates social inequities. In an essay published earlier this year in The New Yorker, staff writer Casey Cep observed: “To diversify historic preservation, you need to address not just what is preserved but who is preserving it—because, as it turns out, what counts as history has a lot to do with who is doing the counting.”

Places associated with African Americans have been lost to disinvestment, urban planning, gentrification and implicit bias. For instance, the Philadelphia Historical Commission rejected the nomination of the Henry Minton House for listing on the local register despite a unanimous vote by the Committee on Historic Designation. The Commission said the nomination met the criteria for designation but the property is not “recognizable” (read: lacked historic integrity). Meanwhile, properties in Society Hill with altered or new facades have been added to the local register.

Do you have a favorite preservation project? What about it made it special?

Robert Purvis was a co-founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society, the Library Company of Colored People and the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. By his own estimate, he helped 9,000 self-emancipated black Americans escape to the North.

The last home in which the abolitionist lived is listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. The property has had the same owner since 1977. As the Spring Garden neighborhood gentrified, the owner wanted to cash in and sell the property to developers who planned to demolish it. The property is protected, so he pursued demolition by neglect. Over the years, the owner racked up tens of thousands of dollars in housing code violations and fines. In January 2018, the Spring Garden Community Development Corporation petitioned the Common Pleas Court for conservatorship in order to stabilize the property. The petition was granted later that year. A historic landmark that was on the brink of collapse was saved by community intervention.

Can you tell us what you are working on right now?

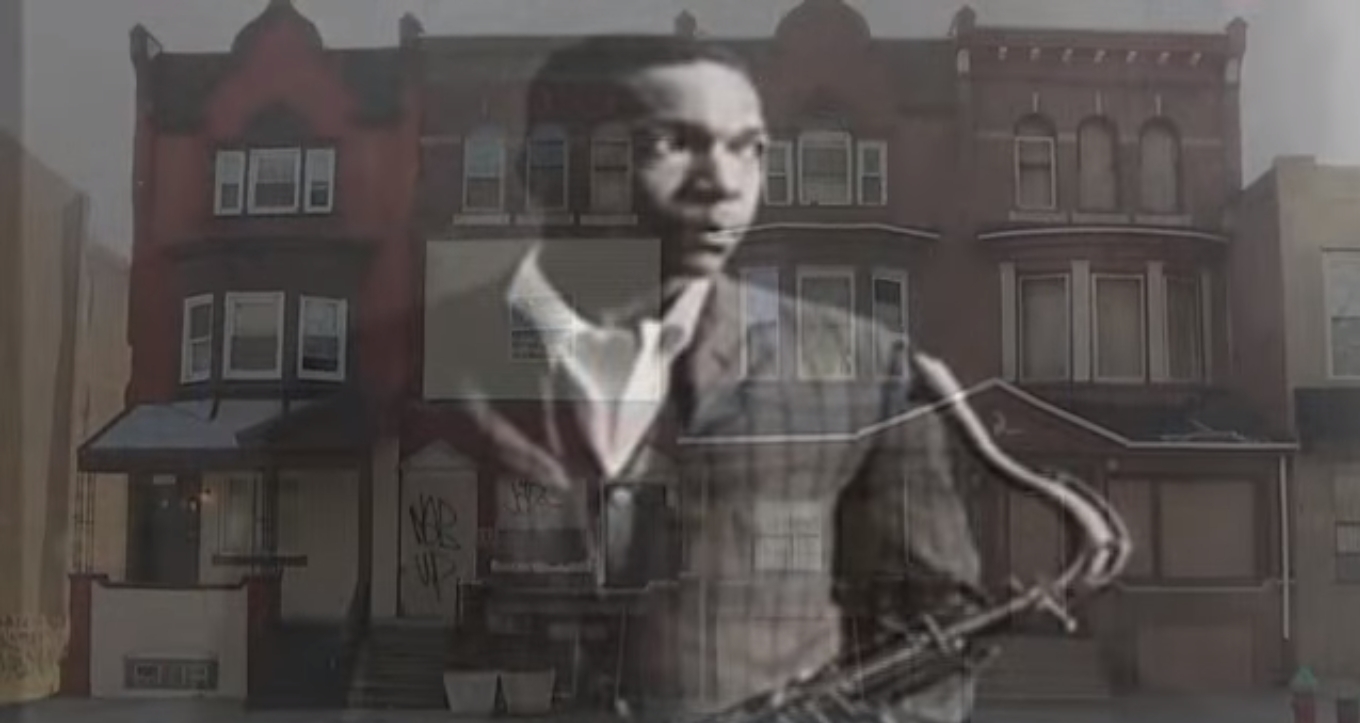

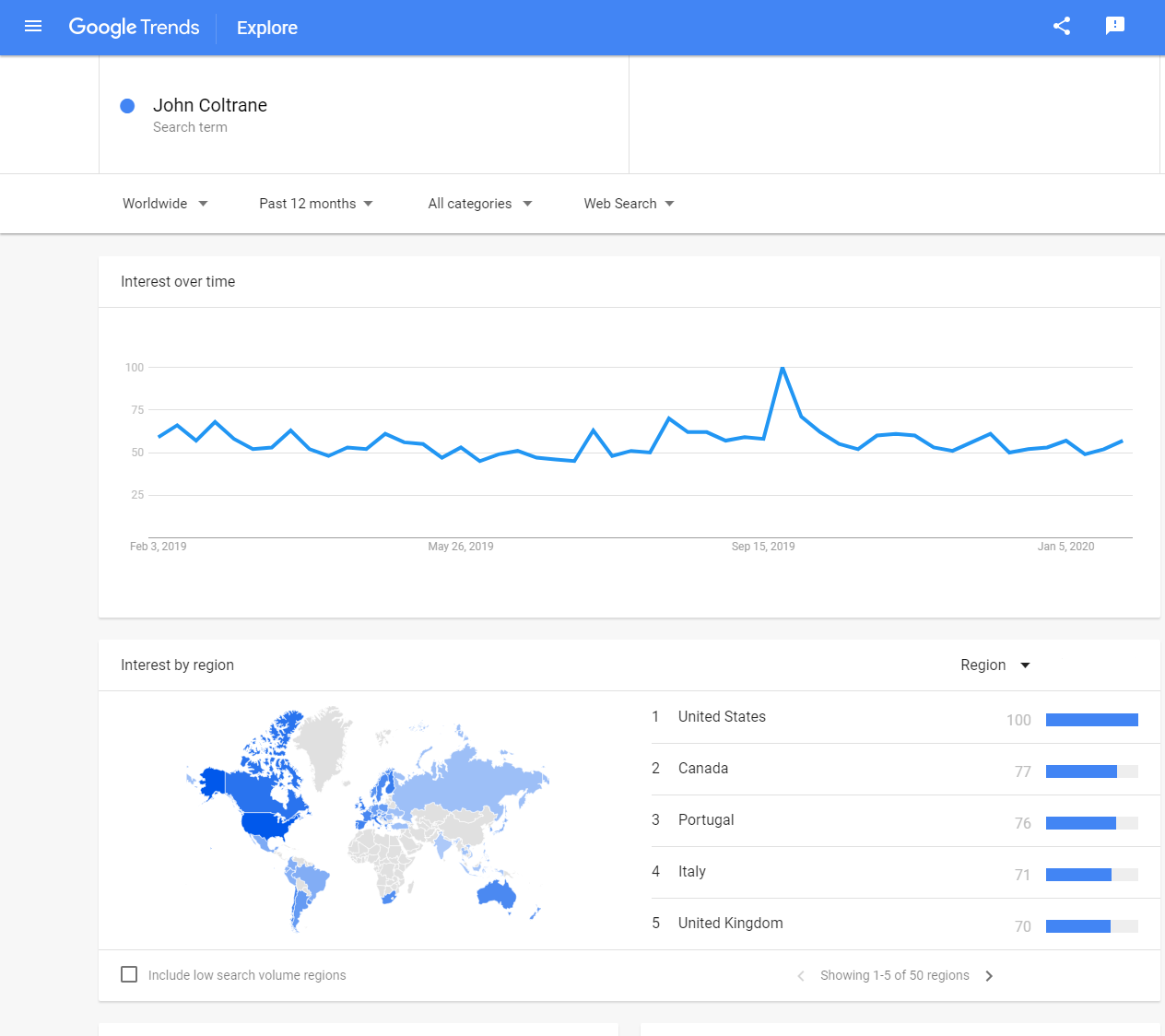

The John Coltrane House, one of only 67 National Historic Landmarks in Philadelphia, is deteriorating before our eyes. In collaboration with the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia, Avenging The Ancestors Coalition and Jazz Bridge, I nominated the historic landmark for inclusion on 2020 Preservation At Risk. The nomination was successful. As hoped, the listing garnered media attention. Before the coronavirus lockdown, several people contacted me and expressed interest in buying the property. The conversations are on pause. I am confident that whether under current “ownership” (the owner of record is deceased), new ownership or conservatorship, the rowhouse where Coltrane composed “Giant Steps” and experienced a spiritual awakening will be restored to its former glory.

Read more