Inducted: 2016

Multitalented and internationally famous jazz legend, – a composer, arranger, lyricist, producer – and tenor saxophonist of world note, Benny Golson was born in Philadelphia, PA on January 25, 1929.

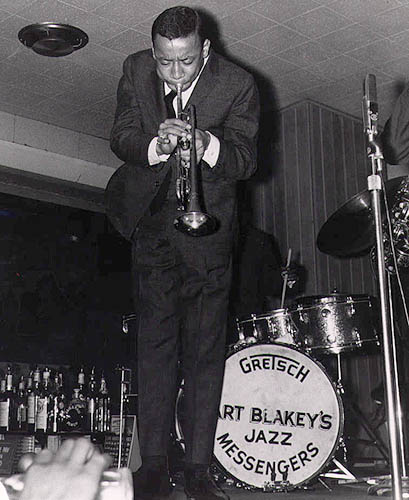

Raised with an impeccable musical pedigree, Golson has played in the bands of world famous Benny Goodman, Dizzy Gillespie, Lionel Hampton, Earl Bostic and Art Blakey.

Few jazz musicians can claim to be true innovators and even fewer can boast of a performing and recording career that literally redefines the term “jazz”. Benny Golson has made major contributions to the world of jazz with such jazz standards as: Killer Joe, I Remember Clifford, Along Came Betty, Stablemates, Whisper Not, Blues March, Five Spot After Dark, Are you Real?

Benny Golson is the only living jazz artist to have written 8 standards for jazz repertoire.

These jazz standards have found their way into countless recordings internationally over the years and are still being recorded.

He has recorded over 30 albums for many recording companies in the United States and Europe under his own name and innumerable ones with other major artists. A prodigious writer, Golson has written well over 300 compositions. For more than 60 years, Golson has enjoyed an illustrious, musical career in which he has not only made scores of recordings but has also composed and arranged music for: Count Basie, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Sammy Davis Jr., Mama Cass Elliott, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, Shirley Horn, David Jones and the Monkees, Quincy Jones, Peggy Lee, Carmen McRae, Anita O’Day, Itzhak Perlman, Oscar Peterson, Lou Rawls, Mickey Rooney, Diana Ross, The Animals (Eric Burden), Mel Torme, George Shearing, Dusty Springfield.

His prolific writing includes scores for hit TV series and films: M*A*S*H, Mannix, Mission Impossible, Mod Squad, Room 222, Run for Your Life, The Partridge Family, The Academy Awards, The Karen Valentine Show, Television specials for ABC, CBS and NBC. Television specials for BBC in London and Copenhagen, Denmark. Theme for Bill Cosby’s last TV show, A french film ‘Des Femmes Disparaissent” (Paris).

Read More