Later this year, Netflix will debut an original documentary about Nina Simone, What Happened, Miss Simone? The film was screened at the Sundance Film Festival.

Rolling Stone reports:

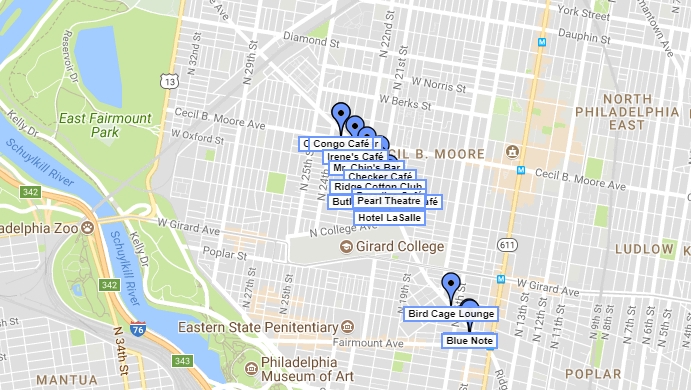

Beginning with footage of the singer staring down an audience at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1976, What Happened goes about answering its question by flipping back to Simone’s childhood, detailing her early musical ambitions to be the first black female classical pianist. Despite her talent and the financial support of well-to-do patrons, she was rejected by the prestigious Curtis Institute in Philadelphia; that “early jolt of racism,” as Simone referred to the incident, became the first of several events to fuel an inexhaustible supply of anger at society. A summer gig at an Atlantic City bar gave birth to the blues chanteuse she’d eventually become, with the film tracing her rise to hit recording artist, jazz sensation, long-suffering wife (her manager/husband Andrew Stroud does not come off well), a major player in the Civil Rights movement, industry pariah, American ex-pat, playing-for-chump-change café performer and, eventually, a rediscovered legend.