The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters were honored at a tribute concert at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

This year’s class includes Archie Shepp who grew up in West Philadelphia. During an NEA interview, Shepp talked about jazz and Philadelphia:

The music that we call jazz has always been important in the African American community, especially in the poorer neighborhoods.

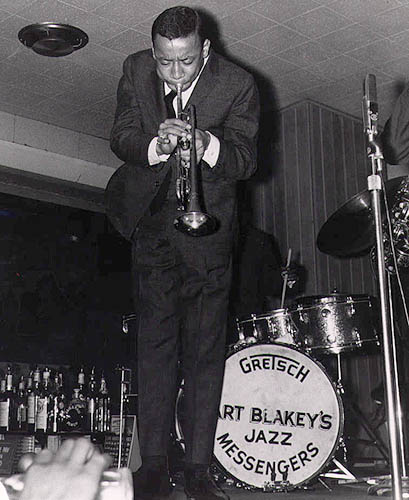

There was a lot of racism and prejudice, but a lot of music, a lot of blues and some good times. Music was all over Philadelphia. You could go down to North Philadelphia and hear young John Coltrane or Johnny Coles, Jimmy Oliver, Jimmy Heath. I suppose that’s what jazz is all about, suffering and good times, and somehow making the best of all of that.

At the tribute concert for Benny Carter, I got a chance to spend some time with Shepp during the break. He reminisced about the jam sessions at the Heath Brothers’ Family Home. He shared that he learned how to play chords from Coltrane and Lee Morgan.

Truth be told, Philadelphia’s contribution to jazz is mostly an untold story. We must capture stories about Philly’s jazz scene while those who know the history are still here.