General George Washington’s decisive victory over British forces in the Battle of Yorktown, aka Siege of Yorktown, was the turning point in the American Revolution. Yorktown, a North Philly neighborhood whose name is derived from the 1781 battle, is under siege.

The planned community was built between 1960 and 1969. Banker and developer Norman Denny acquired 153 acres of blighted blocks that were cleared by the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority. Denny constructed 635 rowhouses that were marketed to first-time African American homebuyers with children. Yorktown provided suburban-style housing for Black families who did not have access to suburban tract houses due to discriminatory lending practices and residential segregation.

In an interview with Scribe Video Center’s Precious Places Community History Project, Bright Hope Baptist Church pastor and former congressman William H. Gray III said:

The church under the leadership of my father who was then the minister, Dr. William H. Gray Jr., got involved with the urban renewal project and joined forces with a man named Mr. Denny of the Lincoln [National] Bank … who had a radical idea. And the radical idea was that instead of building tenements, instead of building tall public housing, what he wanted to do was to build middle-income housing for homeownership. Everybody said you got to be crazy. This is one of the worst slum areas, inner-city, ghetto areas. African Americans don’t have money to buy houses.

Homebuyers included lawyer and civil rights activist Charles W. Bowser who is pictured raising the Yorktown flag. City Council proclaimed October 9, 2018 Charles W. Bowser Day “in recognition of his lifelong dedication to public service and his significant contributions to the African American community in Philadelphia.”

Grammy Award-winning singer Billy Paul lived on Kings Place.

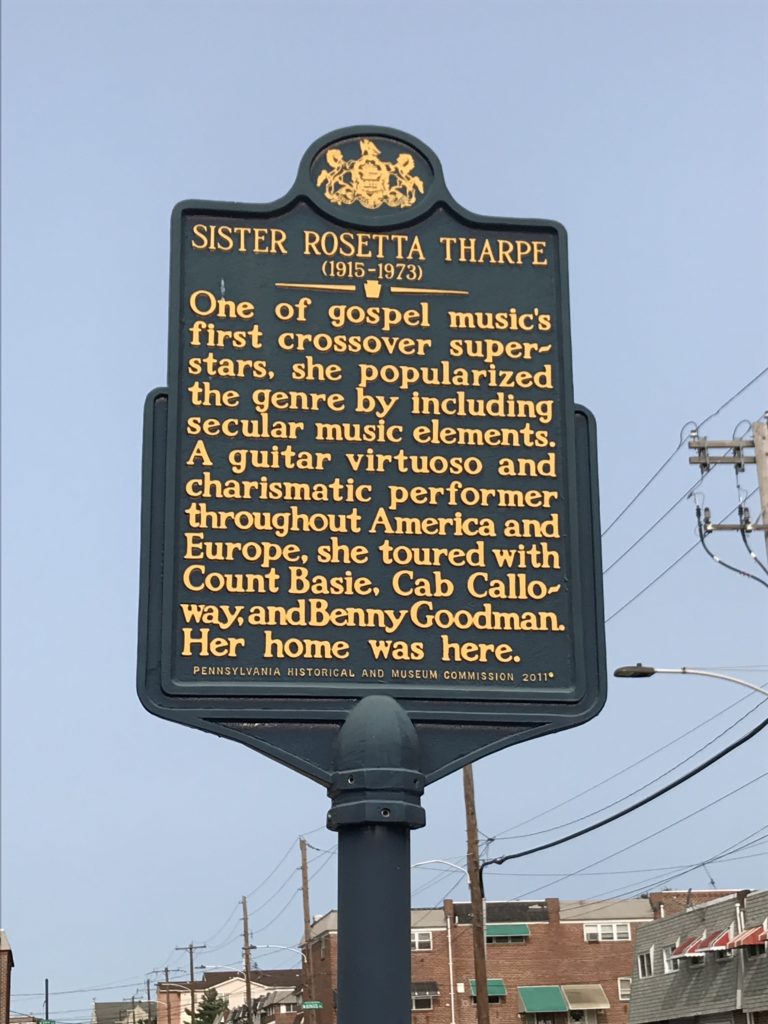

Gospel pioneer and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee Sister Rosetta Tharpe lived on Master Street.

Edmund N. Bacon, then-executive director of the City Planning Commission, planned Yorktown. Landscape elements that Bacon introduced in Society Hill are featured in Yorktown. In a progress report to Mayor James H.J. Tate, Bacon wrote:

Denny has finally put landscaping and play equipment in three of the central squares. These are really remarkable and exciting. I have the feeling that this is a unique project and that nothing of its kind has ever been built. I think it is an achievement worthy of some attention.

The project is indeed worthy of attention. The Yorktown Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2012. It is one of urbanist Bacon’s crowning achievements.

For two decades, Yorktown has attracted unwanted attention. The neighborhood is located immediately south of Temple University. In 2004, the Yorktown Community Organization, founded by Charles Bowser, sued 30 homeowners for illegal conversion of single-family homes into boarding/rooming houses for students. City Council subsequently amended the zoning code to create the North Central Philadelphia Overlay District to, i.a., “preserve and protect the area from the conversion of houses into multi-family buildings that have the potential to destabilize the area; and foster the preservation and development of this section of the City in accordance with its special character.”

Fast forward to today, proposed development projects have the potential to destabilize Yorktown with out-of-scale apartment buildings marketed to students and other transients. The neighborhood is low-rise, low-density by design.

In June, City Council passed legislation to amend the zoning code and create the Girard Avenue Overlay District which would establish height controls. Joe Grace, spokesperson for Council President Darrell Clarke, told PlanPhilly, “The Council President wants to control density along the corridor to protect historic neighborhoods like Yorktown and West Poplar that are adjacent to Girard Avenue. Too much density along the corridors impacts quality of life for the adjacent neighborhoods that are full of single-family homes and long-term residents.”

Black homeowners are fighting to preserve the setting and feeling of the Yorktown Historic District. To paraphrase Revolutionary War Commander John Paul Jones, they have just begun to fight.