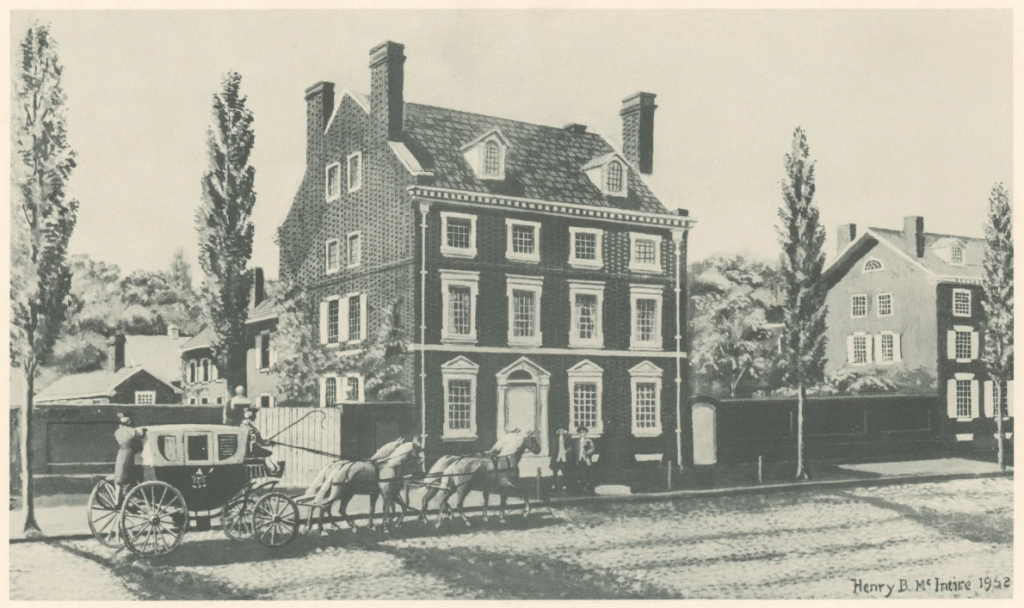

For more than 200 years, the nine enslaved Africans who lived in the Executive Mansion, located at 190 High (Market) Street in Philadelphia, were erased from history. This lost history was uncovered in 2002 and memorialized in the President’s House. The National Park Service site opened on December 15, 2010.

The story of slavery in the shadow of the Liberty Bell was whitewashed from the centennial, sesquicentennial and bicentennial celebrations of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

For the Semiquincentennial, we will breathe life into President George Washington’s enslaved workers and say their names – Austin, Christopher, Giles, Hercules, Joe, Moll, Ona, Paris and Richmond – with joy.

In 1926, a group of women, the Women’s Committee of the Philadelphia Sesqui-Centennial International Exposition, reconstructed Revolutionary era buildings on the fairgrounds in South Philadelphia.

The Daughters of the American Revolution sponsored the George Washington House, aka the President’s House.

The “High Street” exhibit included period-accurate reenactors. The exhibit presented an idealized view of the Revolutionary era. The existence of slavery in the Executive Mansion was left out of the history of 190 High Street.

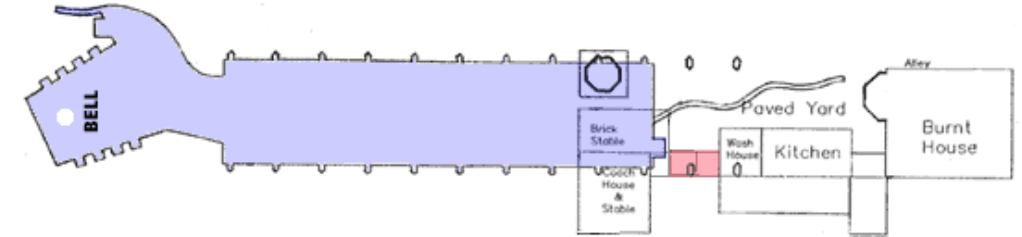

In 2026, a group of activists, architects, technologists and historians will digitally reconstruct the original President’s House and outbuildings.

Instead of reenactors, we will create period-accurate AI avatars of the nine Black people enslaved by President Washington, including his chief cook, Hercules Posey.

In his book, Recollections and Private Memoirs of the Life and Character of Washington, George Washington Parke Custis, the president’s step-grandson, gave a detailed description of an outfit that Hercules wore:

While the masters of the republic were engaged in discussing the savory viands of the Congress dinner, the chief cook retired to make his toilet for an evening promenade. His perquisites from the slops of the kitchen were from one to two hundred dollars a year. Though homely in person, he lavished the most of these large avails upon dress. In making his toilet his linen was of unexceptionable whiteness and quality, then black silk shorts, ditto waistcoat, ditto stockings, shoes highly polished, with large buckles covering a considerable part of the foot, blue cloth coat with velvet collar and bright metal buttons, a long watch-chain dangling from his fob, a cocked-hat, and gold-headed cane completed the grand costume of the celebrated dandy (for there were dandies in those days) of the president’s kitchen.

Custis recalled “the chief cook invariably passed out at the front door.”

The President’s House.ai is currently in development. For more information or to get involved, contact Project Director Faye Anderson at presidentshouseAI@gmail.com.